Recently, top central banks revisited a tool in their tried-and-tested playbook called the foreign exchange swap line. Learn how it helps ensure that financial institutions run smoothly.

FEATURED INSIGHTS

FEATURED INSIGHTSLast March 19, 2023, six major central banks – the US Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB), Swiss National Bank (SNB), Bank of Japan (BOJ), Bank of England (BOE), and Bank of Canada (BOC) – agreed to increase the frequency of their foreign exchange swap lines operations to ensure the availability of US dollar funding worldwide.

What is a forex swap?

A forex swap, also known as a currency swap or FX swap, is a financial derivative transaction in the foreign exchange (forex) market. It involves the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same amount of a currency for two different value dates. The primary purpose of a forex swap is to exchange one currency for another and, at the same time, agree to reverse the exchange at a future date.

How does the forex swap work?

Under the swap lines program, a partner central bank may sell its local currency to the US Fed to purchase US dollars at the prevailing exchange rate. The two institutions then promise to exchange the currencies again after seven days.

This allows the partner central bank to lend the dollars to banks in its respective country that are in dire need of dollar funding. While the Fed is not allowed to lend or invest the foreign currency holdings, it is still compensated by being paid the interest earned on the partner central bank’s dollar loan.

For traders and investors engaged in the USD/PHP forex market, awareness of such swap lines and central bank activities is crucial. These interventions can impact the supply and demand dynamics of US dollars, potentially influencing the exchange rate between the dollar and the peso. Monitoring these developments provides insights into the liquidity conditions and can be considered when assessing forex opportunities in the dollar-peso pair.

The first swap lines were established in December 2007. Initially limited to the Fed, European Central Bank (ECB), and Swiss National Bank (SNB), the swap lines were meant to address a shortage in US dollar funding, as financial institutions were heavily invested in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) – bonds that derived principal and interest payments from US housing loans.

Believing that the US housing market would continue to appreciate, mortgage lenders were aggressively offering loans to borrowers with low income and creditworthiness also known as “sub-prime.”

Eventually, these underlying sub-prime mortgages started to fail, which also caused the bonds to become worthless. Global banks suddenly found themselves scrambling for cash, specifically US dollars. This was the beginning of the global financial crisis (GFC).

How did the Global Financial Crisis affect rates?

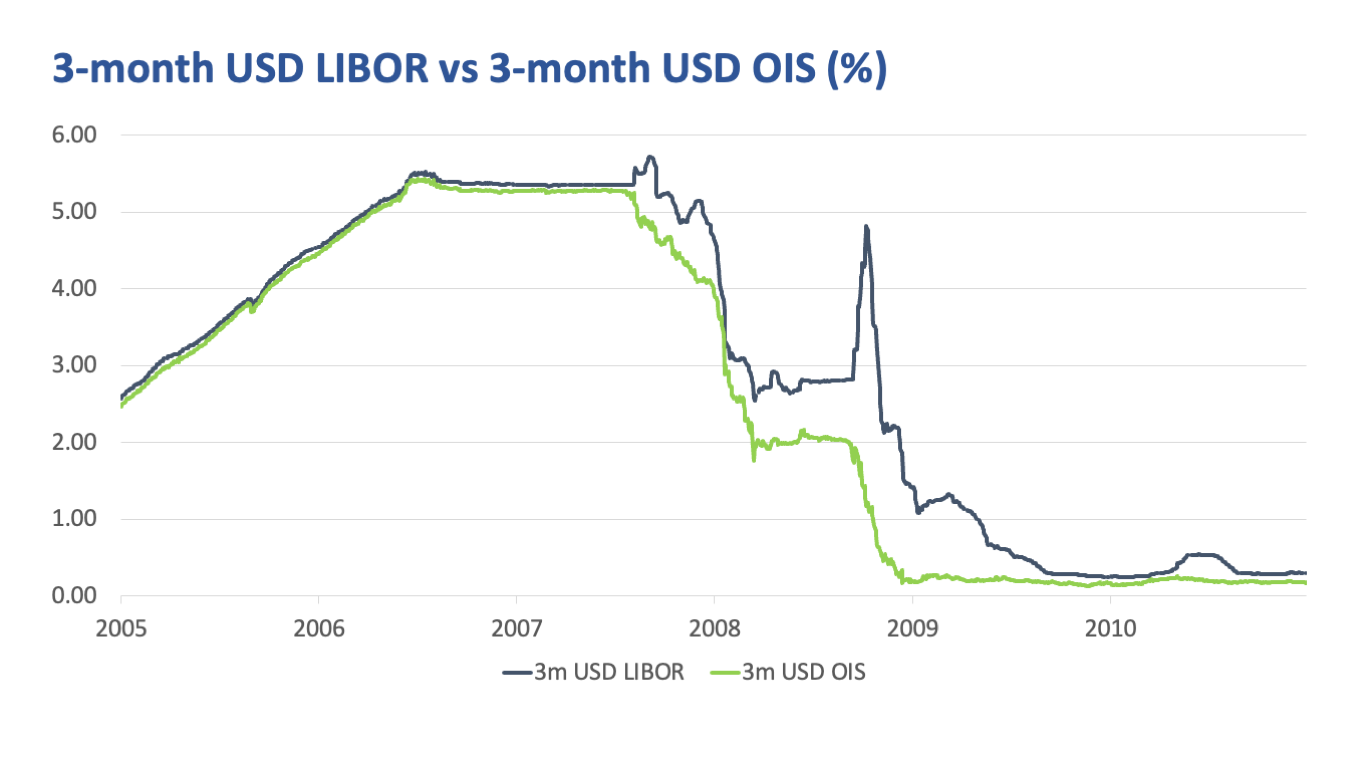

Interbank lending rates surged in response to heightened credit risks, which trickled down into the private sector. There used to be little difference between the 3-month London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) and the US Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS) – a derivative contract that allows banks to swap the Fed Funds Rate for a fixed interest rate and vice versa.

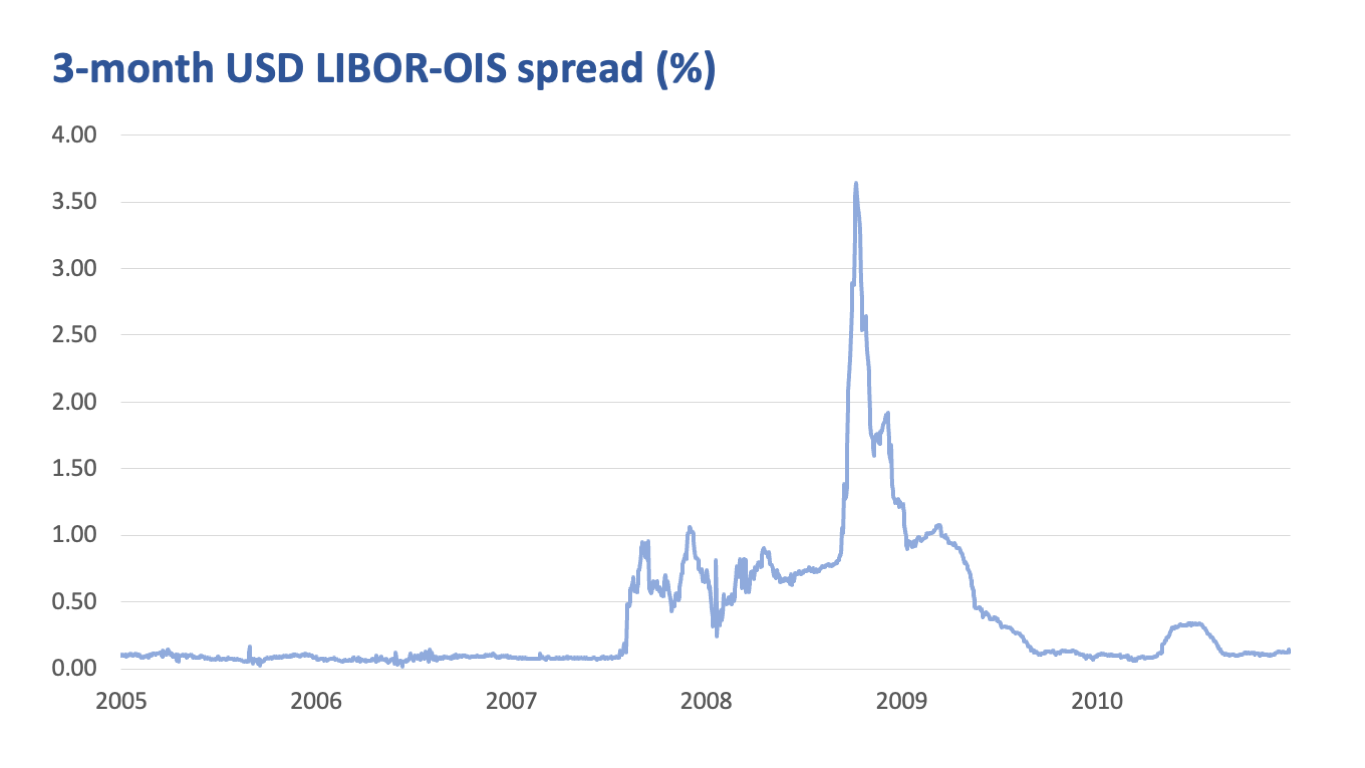

The two rates were parallel with each other, but LIBOR started to break away as dollar liquidity became tight. The difference or spread between LIBOR and OIS was used to measure the willingness of banks to lend. The greater the LIBOR-OIS spread, the greater the perceived credit risk.

The LIBOR-OIS spread continued to widen in 2008 and hit a record high of 350 basis points when US investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September. That same month, the Fed expanded its swap lines to the Bank of England (BOE), Bank of Canada (BOC), Bank of Japan (BOJ) as well as central banks in Australia, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

In October, Brazil, Korea, Mexico, Brazil, and Singapore joined the program. The Fed was able to generate enough US dollars by first selling its holdings of US treasuries. Then as the swap requirements increased, the Fed directly raised funds from the issuance of new treasury bills.

By December 2008, outstanding swaps peaked at more than USD 580 billion, which was equivalent to 25% of the Fed’s total assets at the time. Swap lines saw less and less use in 2009 as access to dollar funding improved. The Fed then ended swap lines operations in February 2010.

What can we learn from history?

The swap lines program was a concerted effort by the major central banks to provide immediate US dollar funding and liquidity to the global financial system. It helped bring market lending rates closer to central bank policy rates once again. The program also prevented central banks and other financial institutions from having to sell off USD-denominated assets, which could have resulted in greater market illiquidity.

After the GFC, the swap lines were reopened in times of financial uncertainty. It was most recently opened again in 2020 in which swaps raised USD 446 billion in funding at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

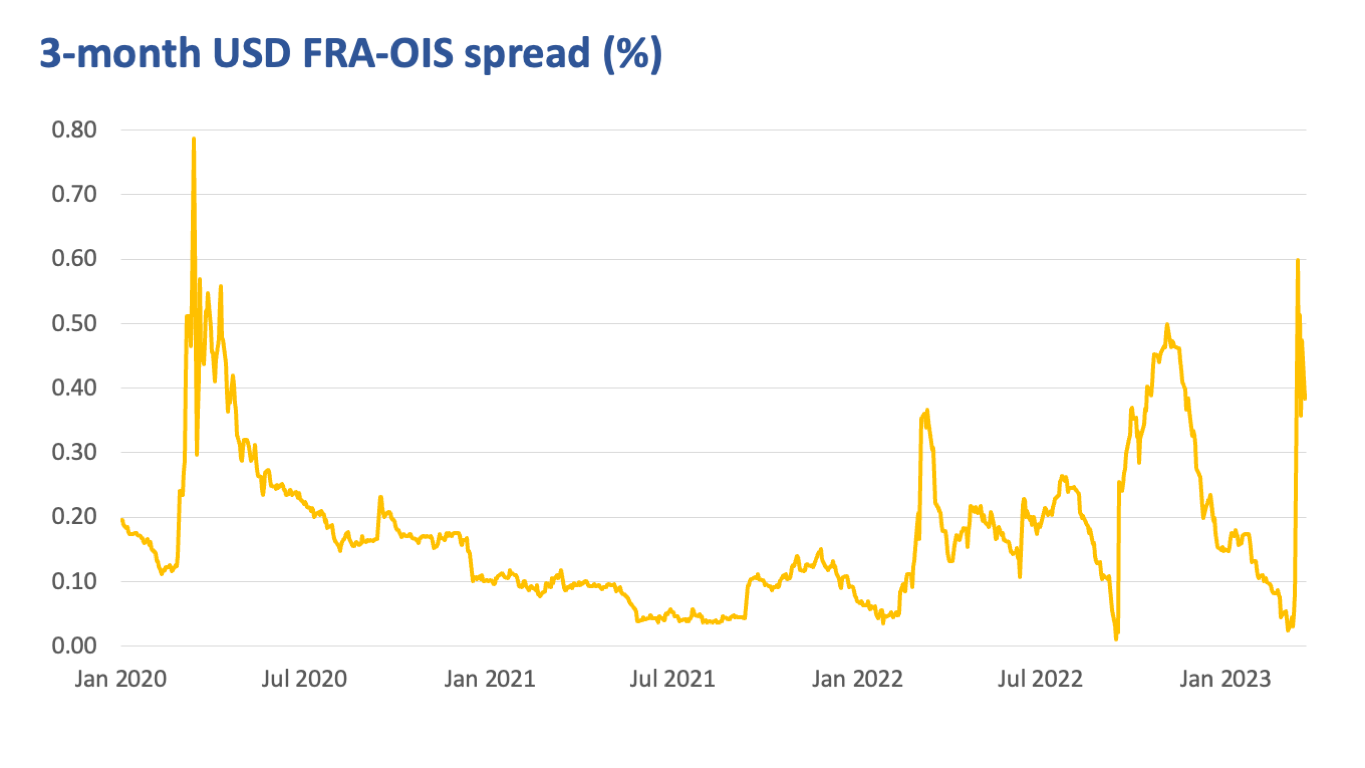

Similar to GFC, market interest rates were breaking away from the Fed Funds Rate. Since LIBOR started to get phased out in 2021, markets instead monitored the spread between the 3-month Forward Rate Agreement (FRA) – derivative contracts which still use LIBOR as a benchmark – and the OIS to measure credit risk. The spread hit close to 0.80% in March 2020 but was still a far cry compared to the record highs observed during the GFC.

Following the bank runs that brought down Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and other regional tech-concentrated banks in the US and the bailout of Credit Suisse in coordination with Swiss regulators and UBS, the FRA-OIS spread is once again at its highest since the beginning of the pandemic.

Markets are once again concerned about the health of the global financial system amid risks of high inflation, slowing business activity, and rising interest rates. But for the world’s top central banks, this is simply a return to the old playbook.

Tried and tested during the GFC, the foreign exchange swap lines program is back to ensure that central banks can provide immediate US dollar funding to financial institutions that need it the most.

Earl Andrew “EA” Aguirre is a Market Strategist at Metrobank’s Financial Markets Sector and has 10 years of experience in foreign exchange, fixed income securities, and derivatives sales. He has a Master’s in Business Administration from the Ateneo Graduate School of Business. His interests include regularly traveling to Japan and learning its language and culture.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By EA Aguirre

By EA Aguirre