In the US, securing a loan has gotten tougher since the US Federal Reserve started hiking interest rates. But the recent banking crisis is raising concerns that lending standards will tighten even further fueling worries of a credit crunch.

FEATURED INSIGHTS

FEATURED INSIGHTSAs Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi said, “credit is the mother’s milk of economic activity.” With slower credit growth, consumers are less likely to spend, while businesses cannot easily expand their operations. This is what a “credit crunch” looks like.

What is a credit crunch?

A credit crunch happens when your bank is unable to lend you money. Tighter credit conditions mean lenders raise the standards for borrowers, and households and firms have to meet stricter conditions to obtain a loan.

When credit conditions tighten, among the first group of borrowers to feel the effects are small businesses and those with poorer credit profiles as banks try to stay away from risk.

What causes a credit crunch?

A credit crunch can be caused by default in loans by borrowers over a long period, resulting in considerable amount in losses for the lenders. Often, the lenders themselves made it easier and more lenient to borrow, which organizations would take advantage.

To lessen the impact on their , lenders would either slow down or stop their lending, or add conditions that make it difficult to borrow money.

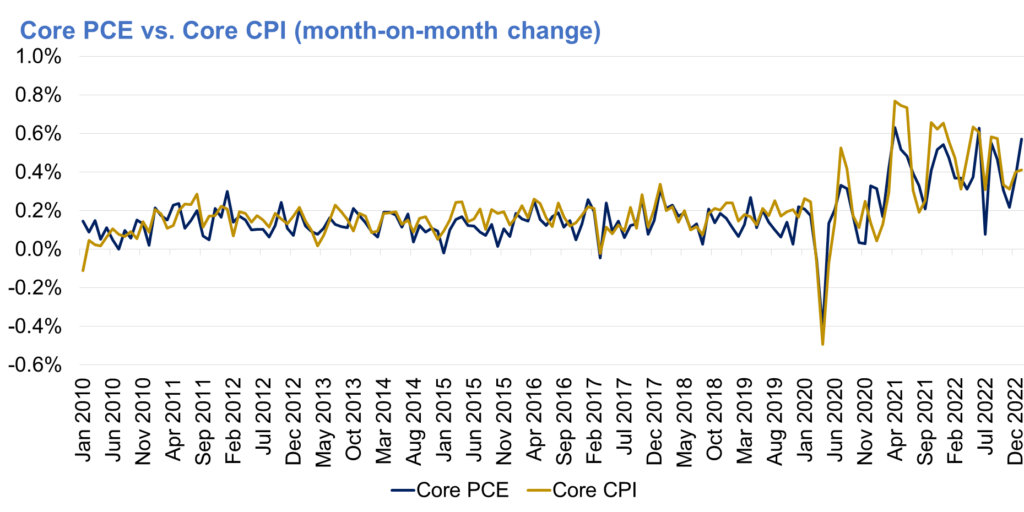

Lending standards were already becoming more restrictive at the end of 2022 amid rising interest rates and ongoing economic uncertainty. Tighter monetary policy makes consumer and business loans more expensive and harder to get.

Yet fears of a potential credit crunch remained elevated in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank’s collapses last month only further raised concerns of a larger financial panic.

Amid contagion fears and to avoid a similar fate, many small and midsize banks have limited their lending to help ensure they have the cash to cover simultaneous depositor withdrawals. Recall that SVB locked up billions of dollars in long-term US Treasury bonds, which lost money as the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates aggressively. So banks now have to prioritize shoring up their balance sheets to weather a potential bank run–a scenario when many consumers withdraw their money from a bank due to a loss of confidence.

What is the effect of a credit crunch?

A cutback in bank lending would mean less spending by consumers and businesses. With fewer loans, it is harder for households to buy cars and houses and for companies to hire new employees and expand their business. These, in turn, would reduce inflationary pressures. Thus, we can say that the US Federal Reserve will get some “help” to slow the US economy and tame inflation.

A Bloomberg Economics model indicated that the market-induced financial tightening, if sustained through June, amounted to the equivalent of 50 basis-points in Fed rate hikes over the rest of 2023. At the same time, a cooling in bank lending flows increases the risk of recession.

Lending standards that are loose can be damaging too. During the 2008 financial crisis, for example, subprime mortgages issued by banks triggered a housing crisis that resulted into a deep recession.

US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said that the recent stress in the banking system may result in tighter credit conditions which may affect the economy. As of late, bank credit growth has declined below the long-term average, with both commercial and consumer loans on a downtrend.

While analysts and surveys believe that a credit crunch has arrived in the US, Fed Chair Powell said the banking system is “sound and resilient, with strong capital and liquidity. We will continue to closely monitor conditions in the banking system and are prepared to use all of our tools as needed to keep it safe and sound.”

The Fed’s next move is yet to be seen if they will put an end to their interest rate-hiking cycle to avoid a recession or continue their regular programming as the US labor market remains tight and inflation is still above target.

GERALDINE WAMBANGCO is a Financial Markets Analyst at the Institutional Investors Coverage Division, Financial Markets Sector, at Metrobank. She provides research and investment insights to high-net-worth clients. She is also a recent graduate of the bank’s Financial Markets Sector Training Program (FMSTP). She holds a Master’s in Industrial Economics (cum laude) from the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P). She takes a liking to history, astronomy, and Korean pop music.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Geraldine Wambangco

By Geraldine Wambangco