So far so good for PH amid overseas banking turmoil

(Last of two parts) In our previous article, we examined how the Philippines managed through the Lehman Brothers debacle. With the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, we now look at possible signs of another “Lehman moment”, if any.

We learned previously that the Philippine banking industry was relatively unshaken post-Lehman as certain banking indicators remained steady. This could not be said, however, for the real economy, which took a hit from the impact of the great recession.

Recently, the world witnessed yet another round of banking turmoil sparked by Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB’s) collapse, which evoked fears of another Lehman moment in the making for the global financial system.

Here, we take a look once more at the recent data and examine whether a similar narrative in 2008 is about the unfold in the Philippine banking sector and the real economy.

PH banking sector: Resilient post-COVID

The Philippine banking sector remains resilient, as evinced by its strong recovery from the COVID pandemic lockdowns. In fact, the COVID pandemic was a much bigger shock to the Philippine banking sector than the Lehman moment of 2008 ever was.

For example, a layman looking at some banking indicators would see the sharp uptick in non-performing loans (NPLs) because of the COVID lockdowns in 2020. However, he would see that this indicator has dramatically come down since then, with the ratio on track to reach pre-pandemic levels.

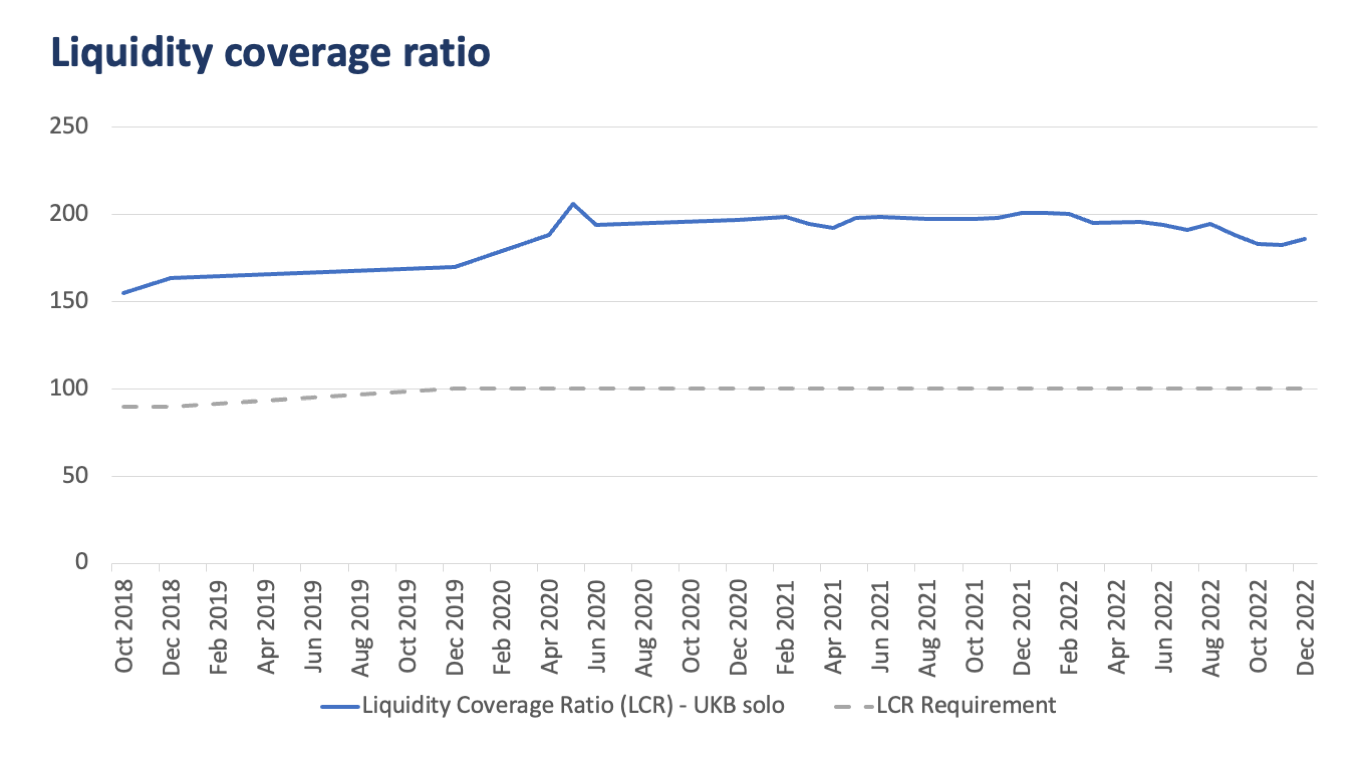

Additionally, a cursory look at the liquidity coverage ratios from pre-pandemic to post-pandemic periods shows that liquidity has always seemed adequate.

The man on the street would likely conclude that if the Philippine banking sector could recover significantly from a much worse event that was the COVID pandemic, then another Lehman-like moment in 2023 is highly unlikely.

That is, just like in 2008, the banking sector will remain resilient. Now, what about the real economy?

The real economy: Expected to remain strong

Recall that rather than the Philippine banking sector being hit badly, it was the real economy of the Philippines which suffered through the Lehman moment of 2008.

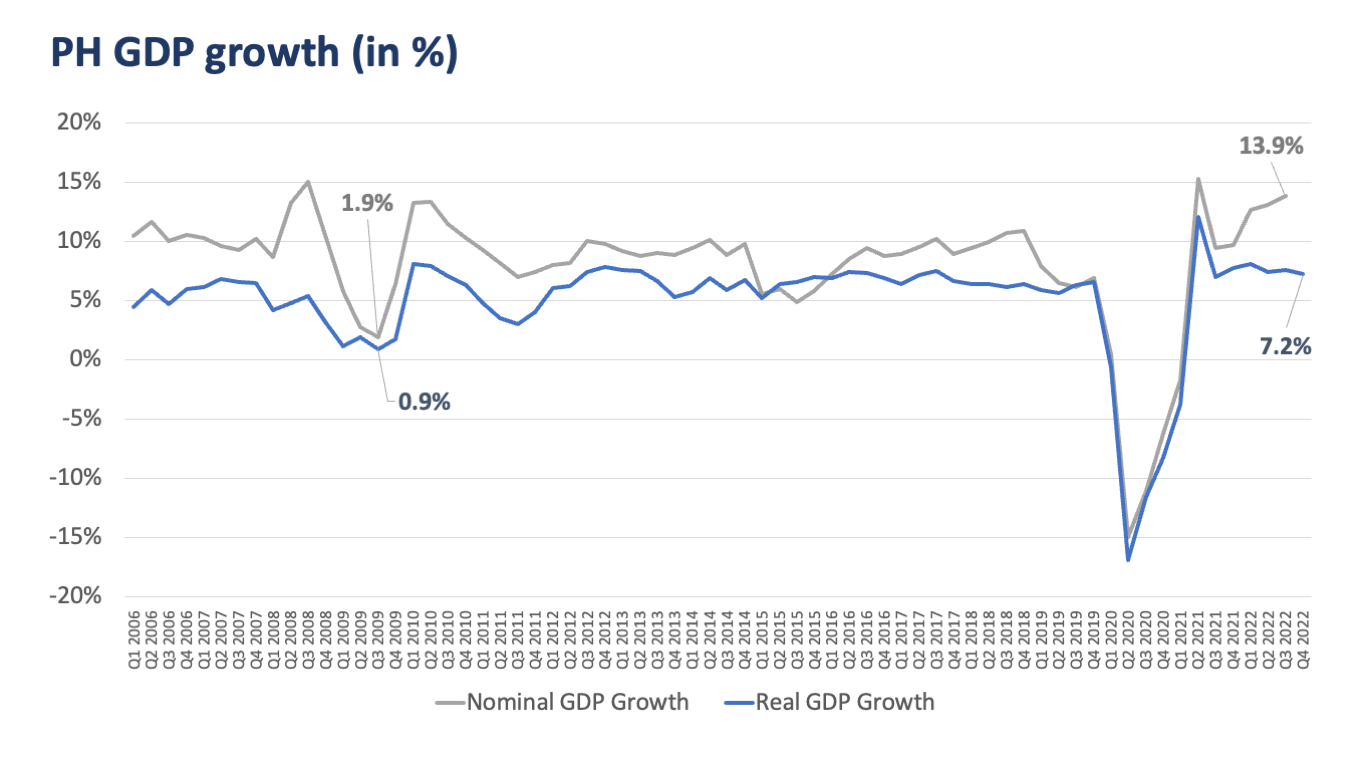

Recently, however, Philippine GDP reached its highest level in over four decades in 2022. Though a slowdown in growth is seen for 2023, the official government forecast is still, at the 6-7% level, satisfactory.

Credit rating agencies, in contrast, have more conservative 2023 PH growth estimates, ranging from 5.7% to 5.9%. Nevertheless, these estimates are still a far cry from the depressed output growth in the post-Lehman period of 2009.

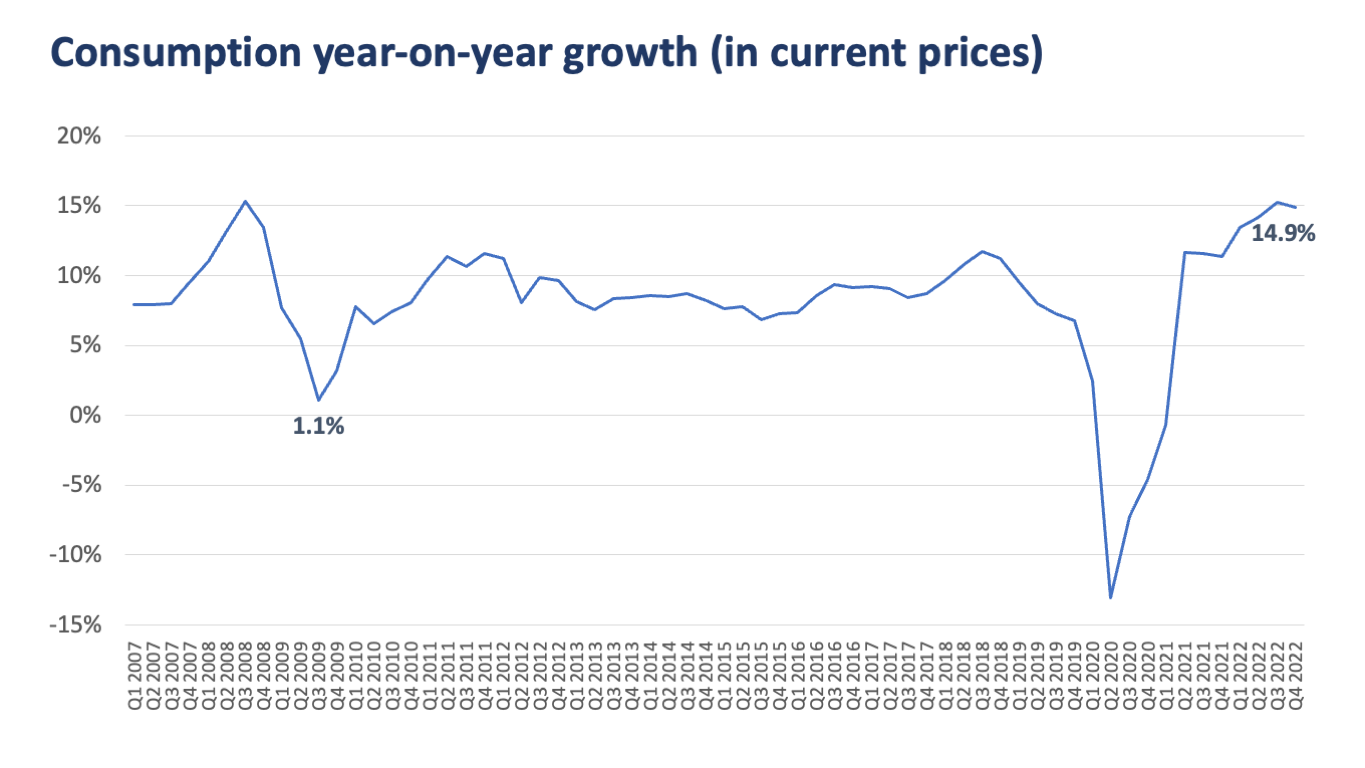

Several signs point to consumption remaining robust. Broadening price pressures were attributed to still vigorous domestic demand. Additionally, credit card debt surged in January, breaching the 30% mark, as well as salary loans, which jumped 67.1%. These are signs that consumption is not slowing down.

Although the latest consumption data is still as of December 2022, the Philippines is still far from the dip experienced in 2009.

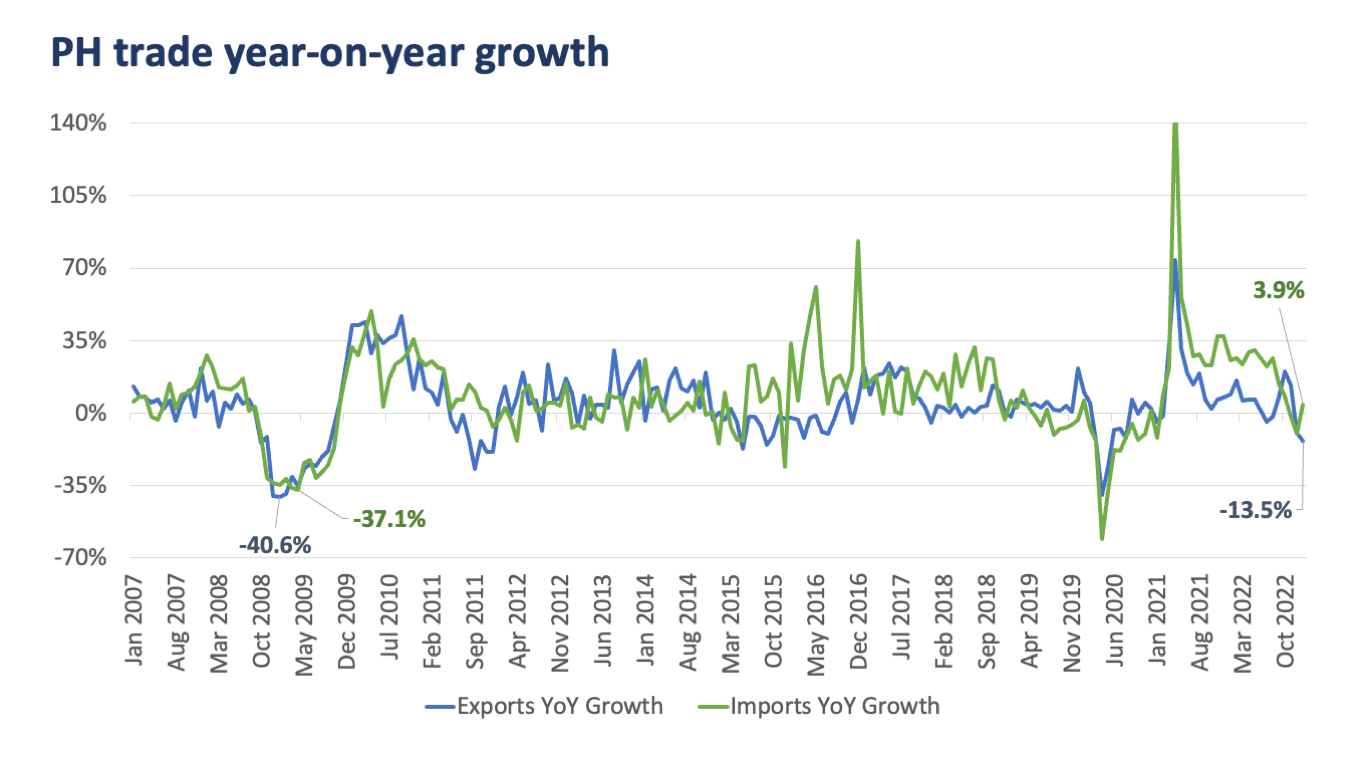

Trade is a mixed bag. Export growth is experiencing a slight contraction on account of weaker global demand due to a slowdown of advanced economies because of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

On the other hand, imports are still expected to grow as the country expands, though possibly at a slower pace.

Given all of these, exports and especially imports are unlikely to go deep into negative territory as in post-Lehman, since the global economy is seen to be tougher than expected.

Several experts expect only a global slowdown as opposed to a recession like before. This will benefit the Philippines due to lower import costs at a time when the domestic economy is expanding, requiring more imports.

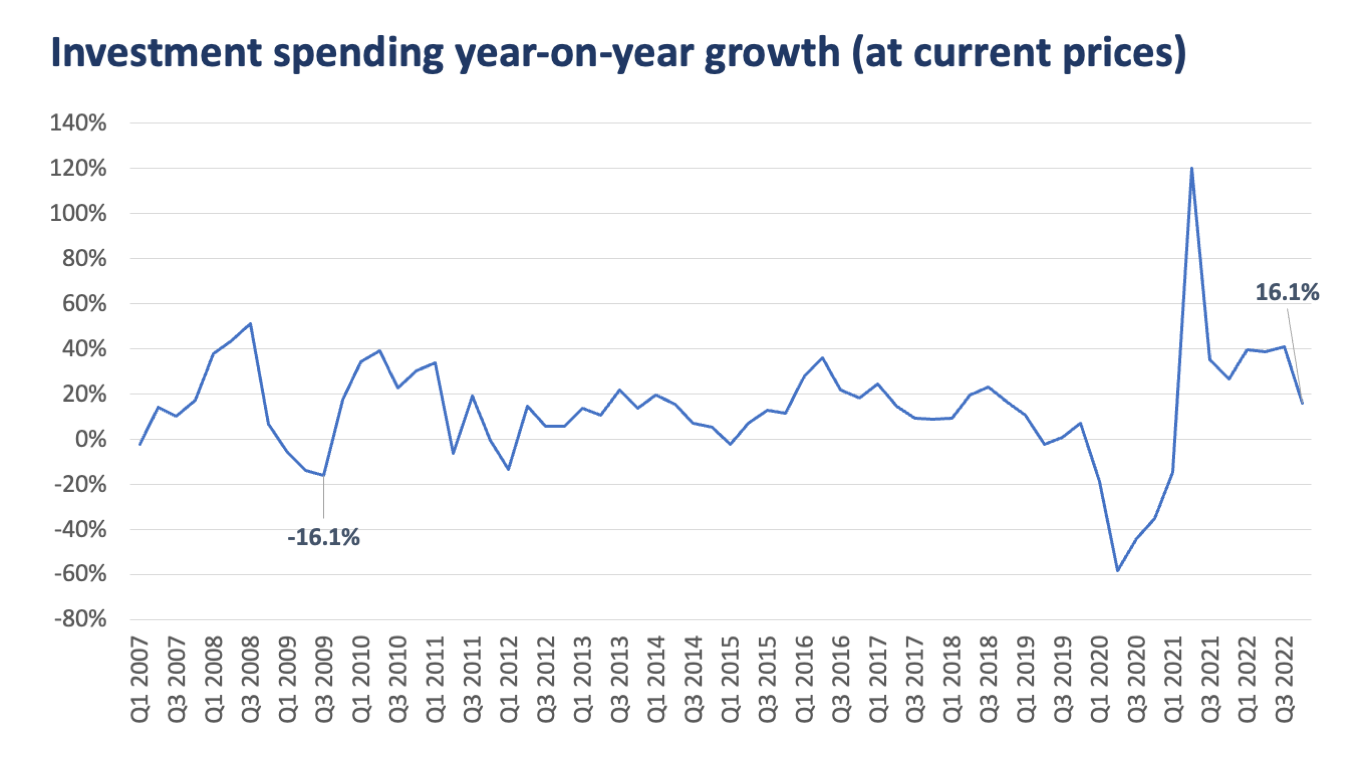

Investment spending is likewise healthy despite rate hikes. Though growth was slower towards year-end 2022, it is unlikely that the country will experience year-on-year contractions given that the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) is signaling a pause in its rate action already, as higher rates are negatively correlated with investment spending.

So far, the macro variables that were hit after the Lehman collapse are still sound at present. In fact, a man on the street would, after seeing the above graphs on the macroeconomy, say that the COVID pandemic was much worse than Lehman.

Wrapping it up: This time it’s different

Putting it all together, it can be said that during the Lehman moment of 2008, the Philippine banking sector was OK while the economy was not.

During the COVID pandemic, both the Philippine banking sector and the economy were severely affected but have recovered significantly since then, demonstrating the resiliency of the local banking sector in particular.

If the SVB collapse morphs into a Lehman moment, we have reason to believe that the Philippine banking sector will remain resilient as before. Additionally, these crises are mainly external to the Philippines, and we don’t think that there will be a difference in the impact domestically.

However, for the economy, the only way the SVB collapse will morph into a Lehman moment is if it causes global trade to collapse, just like what happened in the aftermath of the Lehman fiasco in 2008 and again after COVID struck.

Right now, there appears to be no collapse in global trade, and the failure of SVB (and even that of Credit Suisse) appears to have no spillover effect on global credit and trade.

In this sense, for the man on the street, there’s no reason to worry.

MARC BAUTISTA, CFA is the bank’s Research and Business Analytics Head. ANNA ISABELLE “BEA” LEJANO and INA JUDITH CALABIO are Research & Business Analytics Officers at Metrobank.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Marc Bautista, CFA, Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano, and Ina Judith Calabio

By Marc Bautista, CFA, Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano, and Ina Judith Calabio