Revisiting the collapse of Lehman Brothers

With what’s happening in the banking sector right now, some fear a Lehman-like fiasco waiting to happen. Here we re-examine what happened in 2008 and what lessons we learned.

In our previous article titled Stay Calm, SVB isn’t another Lehman Brothers, we argued that Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) failure does not follow a similar path as Lehman Brothers did back in 2008.

The fall of SVB was an idiosyncratic stress event, driven by aggressive interest rate risk-taking and the mismanagement of this risk by a large but still niche bank. It still pays, however, to be reminded of Lehman Brothers’ cautionary tale that led to the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Lehman Brothers’ collapse nearly 15 years ago is deemed the biggest bankruptcy in US history that marked the beginning of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. What foreshadowed the deepening of the great recession?

What went wrong?

Lehman Brothers, which started as a humble dry-goods store in 1844, grew to become a global financial firm that provided investment banking, trading, brokerage, and other services in the US and globally. It was the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States at the time, even deemed “too big to fail”, with record earnings of more than USD 4 billion on revenues of USD 60 billion in 2007 – the year before its demise.

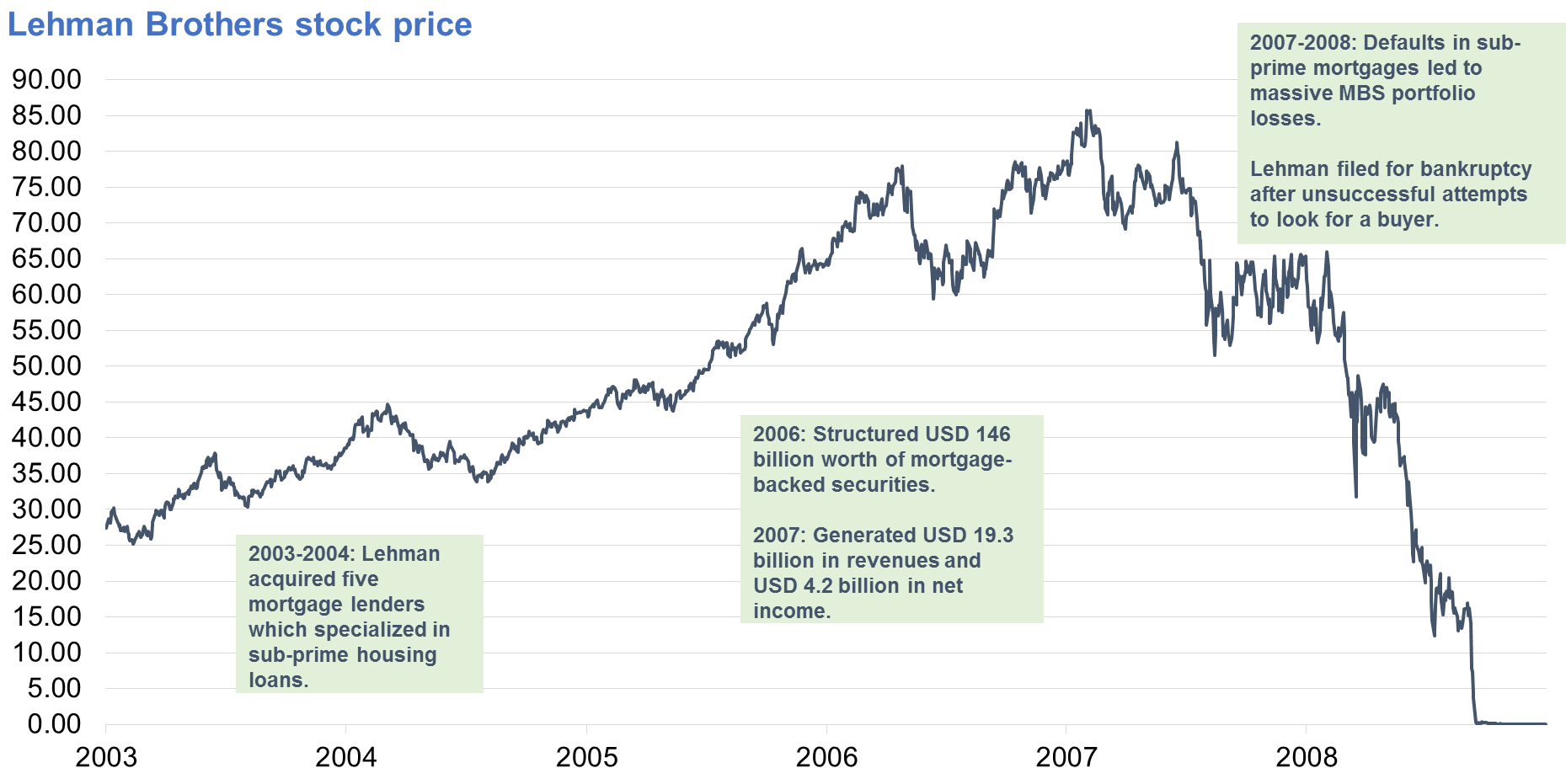

Many reasons point to Lehman falling apart, but the main trigger was its heavy exposure to the US housing market. From 2003 to 2004, the firm invested in mortgage lenders, some of which specialized in sub-prime mortgages or housing loans to individuals with lower credit scores and incomplete documentation, under the guise of greater economic inclusivity.

These lenders provided the underlying housing loans for Lehman’s own mortgage-backed securities (MBS) – bonds that derived interest and principal payments from ordinary Americans’ mortgage payments.

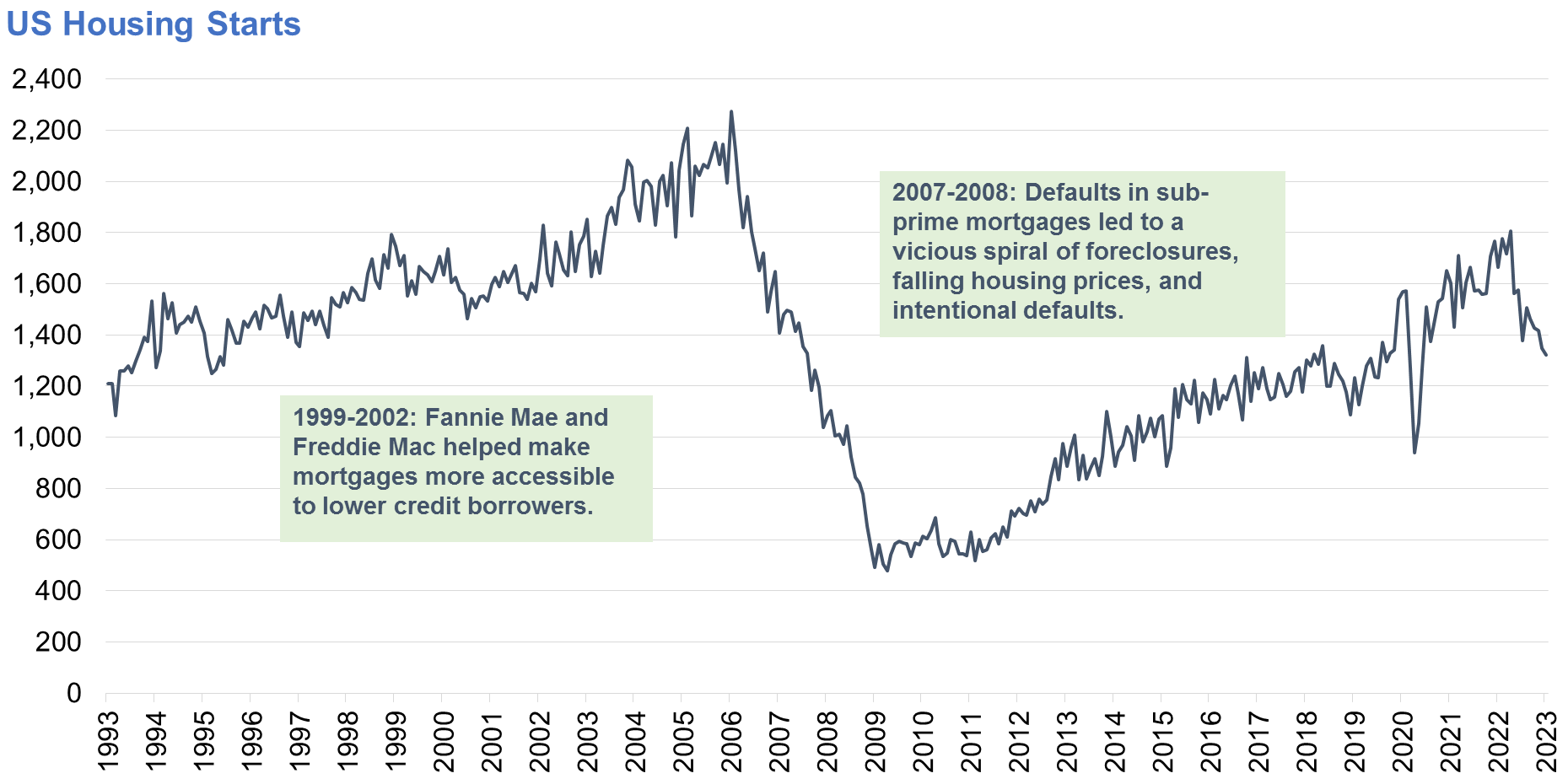

The bonds were popular with high net-worth individuals, institutional investors, and other banks because they offered premium yields and were tied to the US housing market, which continued to appreciate in value. Aggressive lending and MBS structuring activities continued well into 2006, despite the US housing market already peaking.

Lehman Brothers’ stock price peaked in February 2007 and began plummeting in September 2008.

By the end of 2007, Lehman had already acquired USD 111 billion worth of commercial or residential real estate-related assets and securities to which rating agencies and investors expressed concerns over illiquidity.

This left Lehman in a difficult position to bring in cash, hedge risks, or sell assets to reduce leverage in its balance sheet.

Subprime mortgage crisis

While Lehman was aggressively investing in real estate, the subprime mortgage crisis was already brewing. When house prices peaked in 2006, refinancing of mortgages and selling of mortgaged homes became a less feasible means of settling mortgage debt.

Sub-prime mortgages also started to fail in 2007 as borrowers could not keep up with the payments. This led to higher mortgage loss rates for lenders and investors. All of this, coupled with the expansion of mortgages to high-risk borrowers, turned the turmoil into a crisis that ultimately toppled Lehman.

Lehman Brothers invested heavily in high-risk real estate and subprime mortgages and could not raise enough cash when these markets turned south.

No saving by the Fed

Since Lehman Brothers was an investment bank, the US government could not nationalize it like it did with Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation). No regulator like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) could take over. The US Federal Reserve also could not guarantee a loan, as it did with Bear Stearns, another beleaguered bank at that time.

US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson urged then Lehman President Richard Fuld to find a buyer as Bear Stearns had done. Paulson initially rejected Bank of America’s proposal for the government to cover USD 65 billion to USD 70 billion in projected losses.

Federal Reserve of New York President Tim Geithner and the nation’s top bankers spent a weekend trying to find funding for Lehman Brothers. But before they could, Bank of America backed out of the deal. Barclays also announced the following day that its British regulators would not approve a Lehman Brothers deal.

Everyone spent the rest of the day preparing for Lehman’s bankruptcy. Lehman Brothers, with its USD 619 billion in debts, was the largest corporate bankruptcy filing in US history.

Impact of Lehman’s bankruptcy

Lehman’s bankruptcy sent financial markets reeling. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell by as much as 504.48 points and continued to drop until March 5, 2009. Investors also fled to the relative safety of US Treasury bonds, sending prices up and yields down.

Investors knew that Lehman’s bankruptcy threatened the financial institutions that held its bonds. Investors lost confidence in the money market fund when it announced losses of USD 785 billion in Lehman’s commercial paper.

On September 17, 2008, the chaos spread, and investors withdrew USD 196 billion from their money market accounts. The next day, Paulson and Fed Chair Ben Bernanke asked congressional leaders for USD 700 billion, which would allow the Treasury Department to buy shares of troubled banks and bail them out.

Congress rejected the proposal and the Dow went down by 777.68 points. In October 2008, the US Senate voted in favor of a revised USD 700 billion bailout bill that contained a tax cut and extended federal protection for bank deposits.

Who saved Lehman?

Following the bankruptcy filing, Barclays and Nomura Holdings eventually acquired the bulk of Lehman’s investment banking and trading operations. Barclays additionally picked up Lehman’s New York headquarters building.

Lehman’s collapse was a major contributor to what eventually became the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. Many still wonder why Lehman was allowed to fail, rather than being rescued by the US government like so many other banks. One may think of the sheer size of Lehman’s debt and the woeful inadequacy of its assets to cover such debt.

Lessons after Lehman

Greater scrutiny of the financial system followed after the failure of Lehman Brothers and the GFC. In the US, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed in order to subject banks to stress tests, particularly those that were “too big to fail.”

Internationally, banks agreed to set up the Basel-III framework, which required banks to meet higher capital buffers to absorb potential losses, before any profits could be redistributed to shareholders.

Banks were also required to build these capital buffers using their own reserves before they were allowed to source external funding. The crisis resulted in 8 million home foreclosures and a 40% average decline in housing prices.

While some form of subprime mortgage lending still exists today, lenders now require higher upfront down payments and interest rates to compensate them for the risk. Structuring and trading of MBS also continues, but with even stricter regulation and transparency requirements than before. The Fed itself is an active participant and provider of liquidity in the MBS market.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Ina Calabio, Geraldine Wambangco, and EA Aguirre

By Ina Calabio, Geraldine Wambangco, and EA Aguirre