No 2008 redux: containing the Credit Suisse chaos

Before it was Main Street, now it’s Switzerland’s Paradeplatz. We are dealing with a crisis of confidence, not a debt crisis. For now, the forced sale of Credit Suisse has calmed the markets.

UBS Group AG’s government-brokered takeover of its embattled rival, Credit Suisse Group AG, along with coordinated action by the developed countries’ central banks to boost emergency funding, have, in our view, re-established confidence in the global financial system.

It likely averted the tail risk of a full-blown contagion.

We believe that the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank last week were idiosyncratic rather than systemic stress events. Mismanagement of market and liquidity risk is likely to blame. However, the spillover to Credit Suisse, a 167-year-old financial institution that’s been designated as one of the world’s 30 systemically important banks, is a different story altogether.

The risk of contagion and the ensuing market meltdown would be very real if Credit Suisse were to fail, echoing the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, which marked the beginning of the global financial crisis (GFC).

To be clear, the economic fundamentals of 2023 are starkly different from 2008. The world’s largest banks are more resilient due to bigger capital buffers, US business and household balance sheets are healthier, and the US is not (yet) in a recession the way it was on the eve of the GFC, thanks to the boom-bust US housing market.

We don’t have a debt crisis, the textbook cause of financial disasters, but instead a crisis of confidence in the most vulnerable financial institutions. That’s how Credit Suisse came into the picture.

Why Credit Suisse?

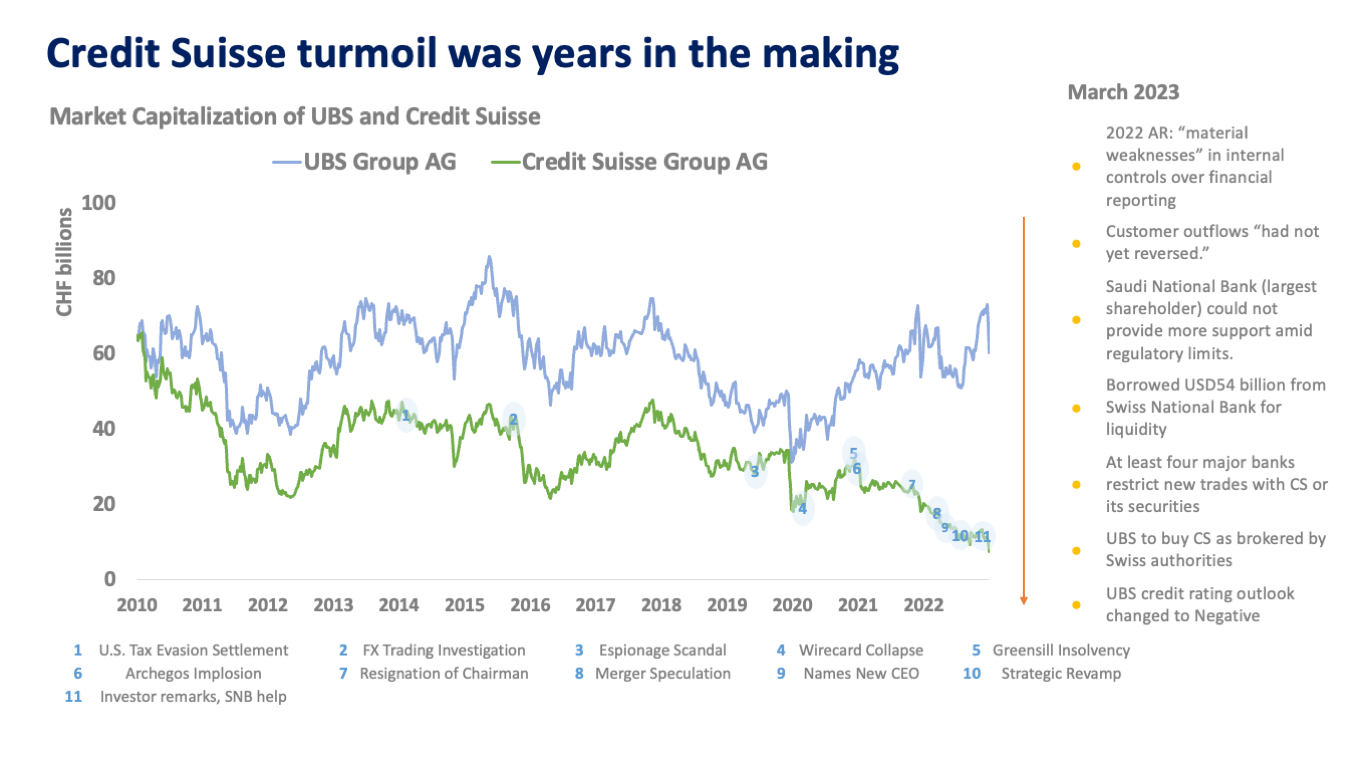

Credit Suisse had CHF 100 billion of capital and hence met the liquidity requirements of a systemically important bank. However, even prior to the collapse of the US regional banks, Credit Suisse was already under a lot of market and regulatory scrutiny thanks to years of losses and high-profile missteps, ranging from high-risk exposures (e.g., the Archegos Fund failure) to cocaine-related money laundering.

The tipping point came on March 15, when Credit Suisse’s largest shareholder, Saudi National Bank, said that it would “absolutely” not increase its investment in the bank. The emergency USD 54-billion lifeline from the Swiss National Bank the following day wasn’t large enough to stem the deposit outflow and panic selling. The Swiss government, with its banking sector teetering on the precipice, had to intervene drastically.

Orderly collapse

The government-brokered sale of Credit Suisse to UBS involved USD 3.3 billion worth of shares, which worked out to only 0.07x of the bank’s estimated full-year 2022 tangible book value, and various government safety nets that included a CHF 100-billion liquidity line from the Swiss National Bank and a CHF 9-billion guarantee for potential losses on some Credit Suisse assets. Importantly, the sale was engineered in such a way that regular shareholder approval on both sides wasn’t required.

The sale also included the complete write-off of USD 17.3 billion worth of Credit Suisse Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds, a condition set by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority to preserve the merged bank’s capital ratios. This likely helped consummate the deal for UBS, which reportedly offered an initial buyout price of at most USD 1 billion against a market cap of USD 8 billion before the weekend.

AT1 bonds are also known as “contingent convertibles” or “CoCo” bonds. They are a form of junior debt that counts towards the banks’ regulatory capital. AT1s are the riskiest and hence highest-yielding instruments, which were designed to transfer risks to investors and away from taxpayers if the issuing bank had trouble. These bonds can be converted into equity or written down when a lender’s capital buffers are eroded beyond a certain threshold.

Calming the markets

The forced sale of Credit Suisse has, for now, calmed markets, but we believe we’re not quite out of the woods yet. We expect volatility to remain elevated near-term as this “mini-crisis” could still lead to other mishaps, including a possible fallout in the AT1 market and more unrealized mark-to-market losses as the US Fed continues to fight inflation with more rate hikes.

Definitely, it’s not a good time to take any outsized bets on higher beta risk assets. It’s better to stay defensive.

RUBEN ZAMORA is First Vice-President and Head of Institutional Investors Coverage Division, Financial Markets Sector, at Metrobank, which manages the bank’s relationships with Non-Bank Financial Institutions, including government financial institutions, insurance companies, and asset managers. He is also the bank’s Financial Markets Strategist, focusing on fixed income and rates advisory for our high-net-worth individuals and institutional clients. He holds a Master’s in Business Administration from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. He is also an avid traveler and golfer.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Ruben Zamora

By Ruben Zamora