Debt-defying strategies: How to stay below the debt threshold

What can the government do to reduce the national debt while upholding a vibrant economy? Let’s talk about it.

Over the past few months, the country’s debt stock level has been growing at a pace that many consider potentially risky.

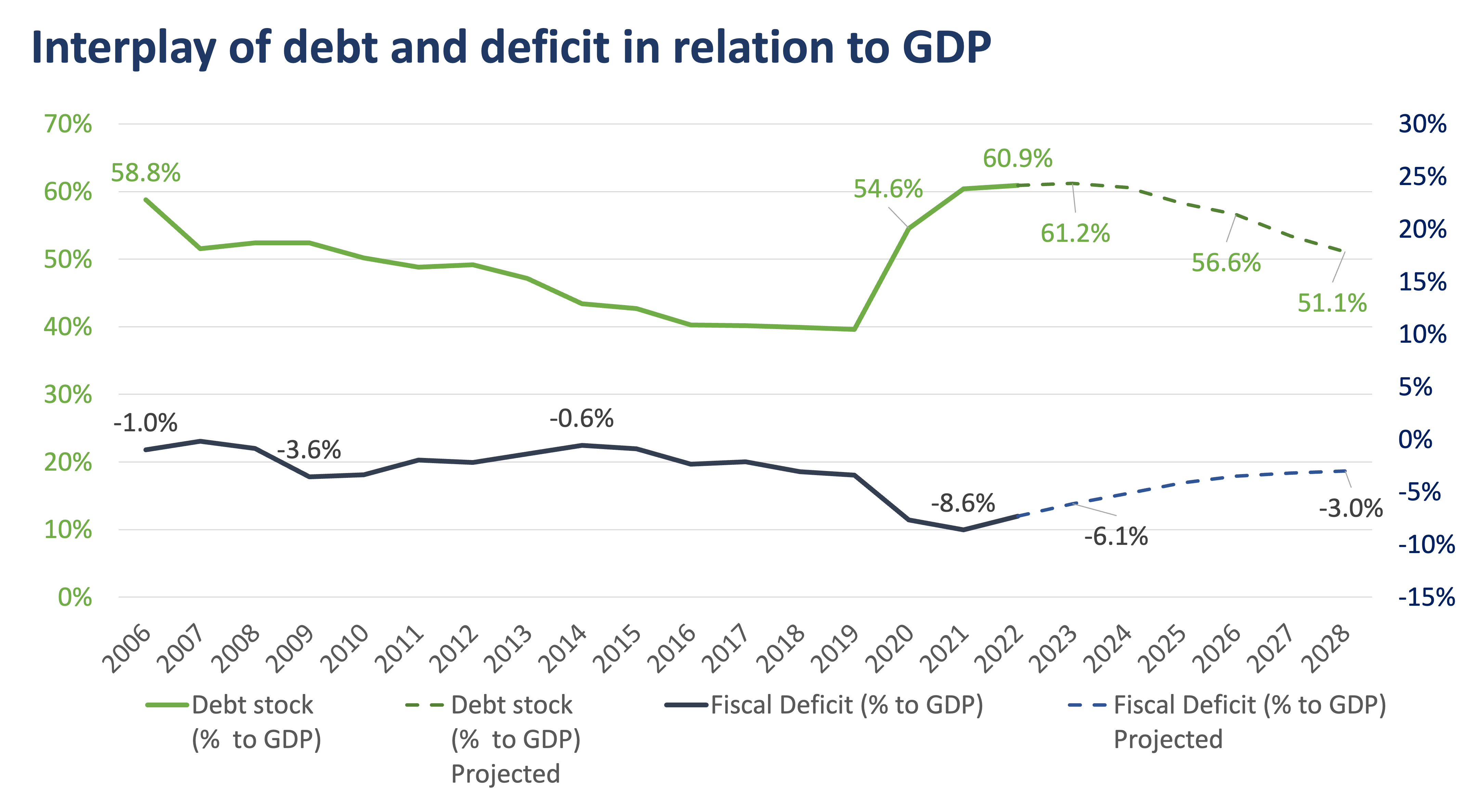

The Philippine debt-to-GDP ratio

In April, it settled at a higher level of PHP 13.91 trillion, growing by 0.4% from PHP 13.86 trillion in March 2023. This has been the Philippines’ highest debt level yet and it can’t be said that it’s going down anytime soon. What led to this surge in debt in the first place?

Since 2006, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio has been well below the so-called threshold of 60%, while the fiscal deficit has been at -3.6% of GDP at the maximum. However, the unanticipated shock triggered by the pandemic pushed the country’s deficit further down, prompting more borrowings to finance a pandemic response and fund the country’s way to recovery while keeping its infrastructure programs going. This then pushed up the debt-to-GDP ratio to levels breaching 60%.

According to a 2022 study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), around half of the debt accumulated in 2020, at the peak of the pandemic, was actually allocated as cash buffers. These funds were part of a precautionary measure in case the pandemic dragged on. The government has reportedly maintained this practice of setting aside cash buffers to date.

The government projections above show that the debt-to-GDP may hover above 60% until next year.

According to a 2022 study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), around half of the debt accumulated in 2020, at the peak of the pandemic, was actually allocated as cash buffers. These funds were part of a precautionary measure in case the pandemic dragged on. The government has reportedly maintained this practice of setting aside cash buffers to date.

More to come, as planned

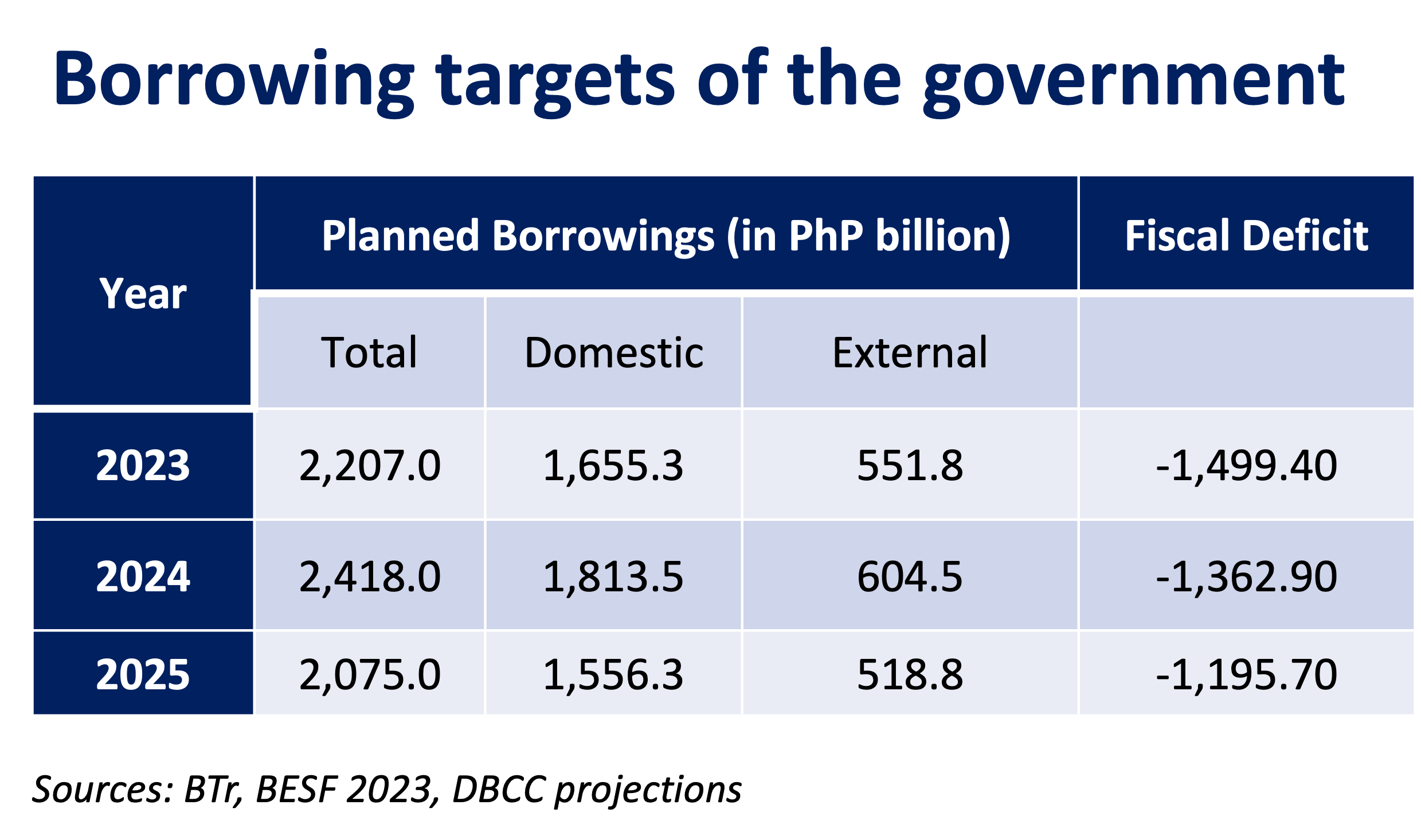

Every year the government sets its target borrowing for the year and the next years, considering its projected deficit and upcoming maturities, among other things.

For 2023, the government intends to borrow PHP 2.2 trillion, from which PHP 1.6 trillion will be sourced domestically, and is bound to grow further in 2024 and slightly decline in 2025, with the deficit seen to gradually ease per year.

A gradual decline in fiscal deficit is expected.

Debt payoff: Maturities ahead

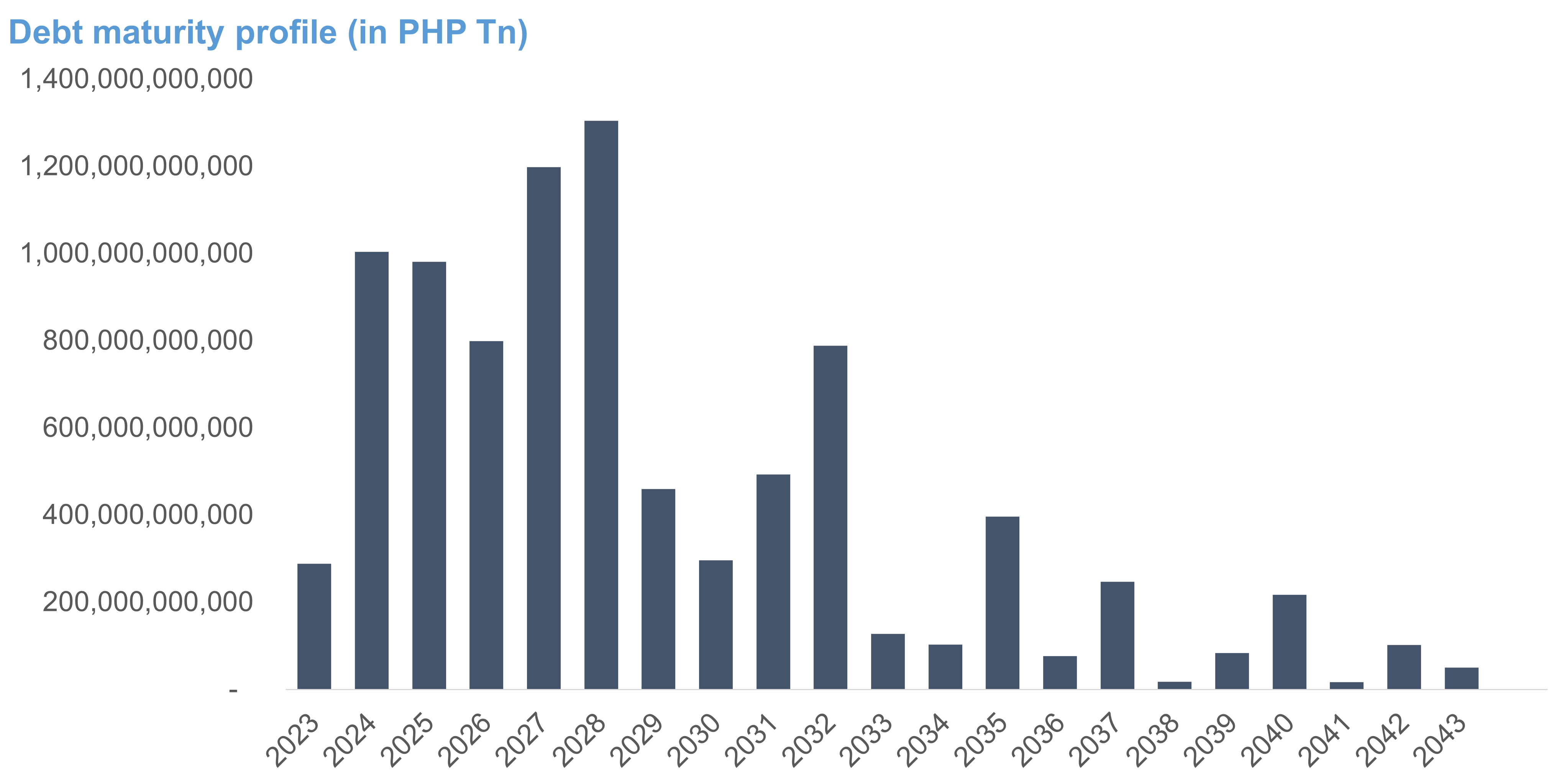

With the Bureau of the Treasury (BTr) already fulfilling 69% of the government’s borrowing program as of end-May, there is a few years’ worth of maturities that is needed to be pre-funded. The Philippines’ debt maturity profile shows that the BTr has room to issue another Retail Treasury Bond (RTB) as early as next month ahead of the first chunky maturity in August worth PHP 141 billion, followed by a PHP 144 billion in September.

The government has a bit of room to issue for 2026 (3 years), 2029 (6 years), and 2030 (7 years). It is also possible that they will issue an odd-tenored RTB (e.g., 5.5 or 6.5 years) just like last April with Fixed Rate Treasury Note (FXTN) 13-1, the first series of its kind. We therefore expect sizable issuances in order to pre-fund these maturities.

The Bureau of the Treasury has room for sizable issuances for the government’s budgetary needs.

How to reduce national debt: An analysis

Over the next years, the country’s Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF) aims to lower the debt-to-GDP and deficit-to-GDP ratios simultaneously.

Analysts and economists alike acknowledge that there’s still a long way to go before the country’s debt goes back to comfortable levels, even challenging MTFF’s targets by 2028, considering upcoming maturities, projected deficits, and infrastructure projects that will need funding.

The good news, however, is that the country’s current debt situation driven by the pandemic is not as deep-rooted, or even self-inflicted as in past debt episodes, and is therefore manageable. How can this be attained? According to studies, analysts’ views, and our own analysis, here’s how:

- Strategic utilization of accumulated cash buffers. The utilization of debt to accumulate cash buffers, which was earlier mentioned to be around half of the debt accumulated during the height of the pandemic, creates the potential for a significant reduction in future debt. By subtracting the government’s cash reserves, the debt-to-GDP ratio’s behavior would exhibit a similar pattern, but at a significantly lower level.

- Grow, grow, grow. Another approach to gradually decrease the debt-to-GDP ratio is, of course, to expand the denominator, the GDP, at a faster pace than the numerator, which is debt. As GDP growth improves, the debt burden will naturally decline over time. Encouragingly, GDP growth has already surpassed pre-pandemic levels in 2022 and is poised to follow its pre-pandemic trajectory from hereon. This should be combined with minimal acquisition of substantial new debt.

- Channel debt into high-yield investments for maximum impact. Furthermore, to get the economy rolling, governments must keep spending. It’s like injecting energy into the system, and this is why debt is incurred. But focus should be on areas such as human capital (i.e., education and skills) and infrastructure that create multiplier effects on the economy, generating more jobs and benefits, leading to a proportionally larger increase in national output vis-à-vis the amount spent.

- Avoid policy reversals. In addressing the mounting debt, it’s vital to understand that the pandemic, not flawed policies, drove its recent surge. To rein in the debt, PIDS emphasizes the need to steer clear of policy reversals that hinder income generation, lead to unwarranted increases in government spending (such as expansive entitlement programs), and undermine previous pre-pandemic debt reduction measures.

- Have clear fiscal rules. In a study done by Esquivel and Samano in April 2023, it was recognized that having debt rules creates confidence in financial markets, leading to lower sovereign spreads or lower interest rates on government loans. The rollout of the country’s MTFF last year instills confidence in the market, helps stabilize expectations, and sets the stage for lower sovereign spreads which can ease the debt burden.

Implementing these strategies can effectively tame debt and improve the debt-to-GDP ratio, unless, of course, there are unforeseen macro-fiscal disruptions such as a sudden economic downturn (e.g., sudden surge in COVID-19 cases), natural calamities demanding significant expenditures, or adverse currency and interest rate fluctuations triggered by higher US rates, leading to currency depreciation, potentially amplifying foreign debt obligations, and escalating the burden of debt servicing.

Pushing the limits

Despite the potential challenges and risks mentioned, we remain optimistic about the Philippines’ future. With anticipated robust growth, sustained infrastructure spending and other investments which generate multiplier effects, and hopefully prudent fiscal governance, we expect a gradual decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

While the timeline may extend beyond government projections, the goal of going below the “debt threshold” appears within reach.

INA JUDITH CALABIO is a Research & Business Analytics Officer at Metrobank in charge of the bank’s research on industries. She loves OPM and you’ll occasionally find her at the front row at the gigs of her favorite bands.

ANNA ISABELLE “BEA” LEJANO is a Research & Business Analytics Officer at Metrobank, overseeing research on the macroeconomy and the banking sector. She earned her BS in Business Economics degree from the University of the Philippines Diliman and is currently pursuing her MA in Economics at the Ateneo de Manila University. In her free time, Bea enjoys playing tennis and spinning. She cannot function without coffee.

GERALDINE WAMBANGCO is a Financial Markets Analyst at the Institutional Investors Coverage Division, Financial Markets Sector, at Metrobank. She provides research and investment insights to high-net-worth clients. She is also a recent graduate of the bank’s Financial Markets Sector Training Program (FMSTP). She holds a Master’s in Industrial Economics (cum laude) from the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P). She takes a liking to history, astronomy, and Korean pop music.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Ina Judith Calabio, Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano, and Geraldine Wambangco

By Ina Judith Calabio, Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano, and Geraldine Wambangco