China’s deflation situation: Is it another Japan-like story?

China recently went to deflation which led to comparisons with Japan’s decade-long struggle with deflation in the 90’s. What are the parallels between the two powerhouse economies and do signs point to another deflation crisis in the making?

As most economies grapple with stubbornly elevated inflation globally, China recently reported a drop in its consumer price index (CPI). Its July CPI inflation fell by 0.3% year-on-year, thereby bringing its economy into deflation.

This triggered worries of another deflation crisis like Japan’s in the 90’s that may have rippling effects to the global economy.

Drivers of China’s deflation

China’s recent negative inflation growth was driven primarily by decreasing transportation and food costs, which account for 14.5% and 20% respectively of its Consumer Price Index (CPI). Easing energy commodities (and access to Russian oil) have translated to lower transportation costs while a recovery from African swine fever resulted in an oversupply of inventory in the world’s largest producer and consumer of pork.

It would be premature to call this trend deflationary since core CPI, which excludes volatile energy and food prices, still grew by 0.8%. But it cannot be denied that China’s recovery since the end of its lockdown has been disappointing.

It can be recalled how global investors were ecstatic when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced the end of its Zero-COVID policy in December 2022. The world’s manufacturing hub back in operations meant more efficient supply chains, which would help reduce costs, especially in countries that were still dealing with elevated supply-side inflation.

Consumer spending was also expected to explode as Chinese citizens were finally free to leave their homes and travel. However, the country started to realize the consequences of its prolonged lockdown.

Multinational corporations already started to diversify their manufacturing plants in other Asian countries such as India and Vietnam, leading to declining Chinese exports and jobs. Exports fell by 14.50% year-on-year in July versus -12.40% the previous month. While unemployment decreased to 5.30% from its 6.20% high in 2022, an alarming 1 in 5 young adults (16 to 24 years old) in urban areas remains unemployed.

Private sector investment spending also remains depressed. New bank loans and aggregate financing, a broader measure of credit, were only at CNY 345.9 billion and CNY 528.2 billion respectively from a staggering CNY 3.05 trillion and CNY 4.22 trillion the previous month. The lack of demand for real estate threatens China’s property sector, whose companies have started to default on their bond payables.

To make matters worse, the US President Joe Biden advocated to limit investment into China’s technology sector, citing national security issues.

Japan: The Bubble Economy

China’s problems today were compared to those of neighboring Japan in the early 1990s. Labeled the “Japanese Economic Miracle,” the country quickly recovered from its loss in the Second World War to become a technological and industrial powerhouse. Japanese electronics and automobiles were high quality yet inexpensive, so much so that the United States, which accounted for 40% of Japan’s exports, was quickly incurring a trade deficit.

In 1985, the Plaza Accord was signed – an agreement that would allow foreign exchange intervention to devalue the US dollar and help reduce the US’ growing trade deficit. The USD/JPY exchange rate fell from a high of 200 to the 128-level by 1987. With the stronger yen threatening to make Japanese exports less competitive, the government and central bank cooperated to boost public spending and ease monetary policy to drive up domestic demand. From 1986 to 1987, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) cut its policy rate by 200 basis points (bps), from 5.50% to 2.50%.

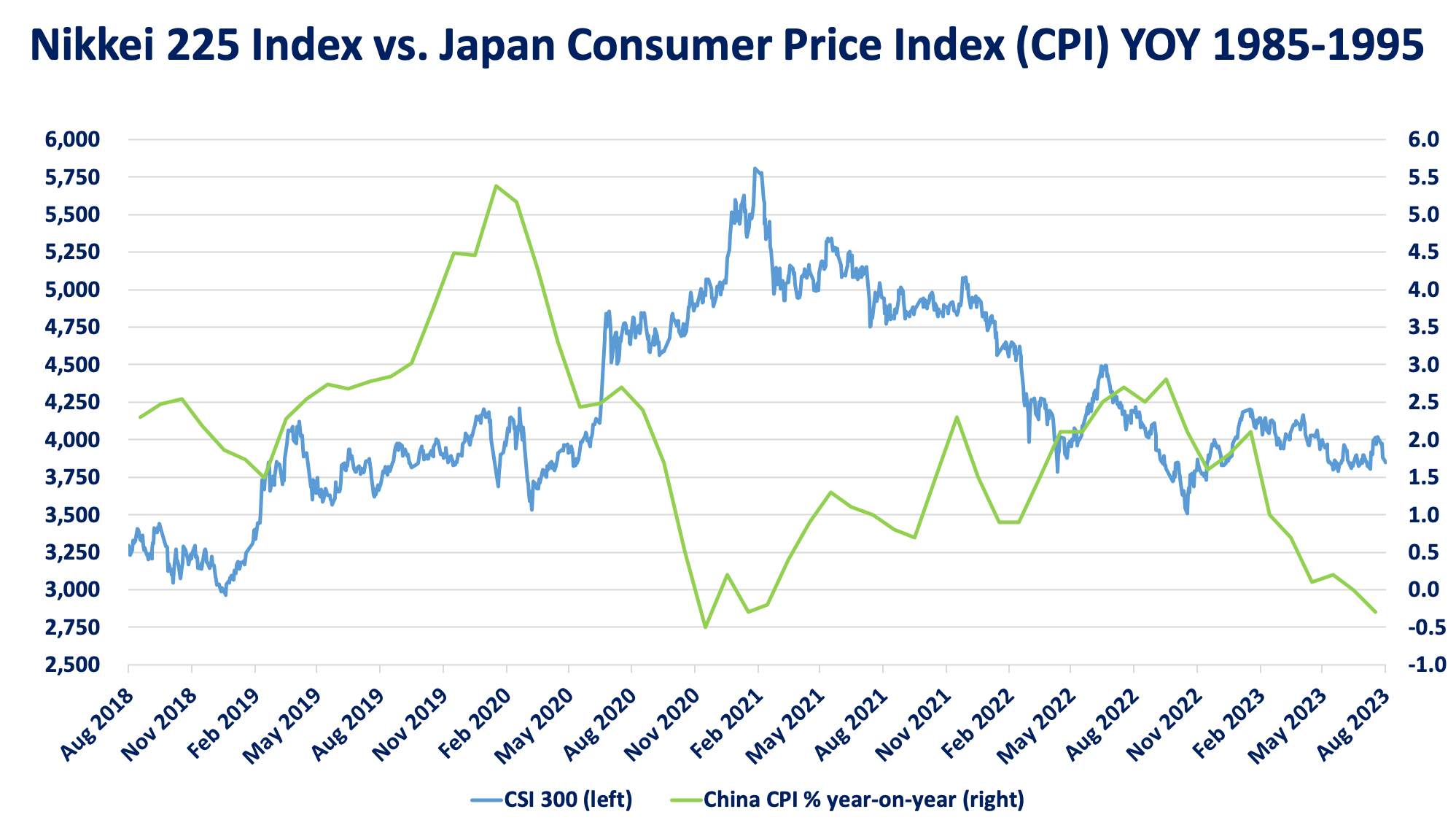

Easy access to cheap capital resulted in a growing asset bubble that saw Japanese corporations and individuals alike speculating on real estate and the stock market. From January 1985 to December 1989, the Nikkei 225 Index grew by almost 237%. By this time, Japanese corporations were profiting more from trading and positive revaluations while their core businesses started to lose to foreign competitors. Increasing asset prices allowed borrowers to assign larger amounts of collateral which led to an unending cycle of even greater borrowing and spending.

Japan’s inflation jumped to 2.4% year-on-year by April 1989 from a full-year average of just 0.68% in 1988. In response, the BOJ started a series of rate hikes totaling 350 bps that brought its policy rate to 6% by August 1990.

The shift to monetary tightening caused the asset bubble to burst, with property and stock prices falling in the years that followed. Declining asset prices resulted in growing debt ratios and unattractive balance sheets, further exacerbating the sell off. The Nikkei 225 Index dropped 63% from December 1989 to August 1992.

Chart 1. Nikkei 225 Index vs. Japan Consumer Price Index (CPI) year-on-year 1985-1995

The crisis eradicated as much as USD 2 trillion in value and left the Japanese in debt. Households prioritized saving which forced businesses to slash prices on goods and services to generate sales. This resulted in consistent disinflation which turned into deflation when the consumer price index (CPI) entered negative territory in 1995. Wages remained stagnant and businesses were forced to lay off workers, with the unemployment rate hitting a high of 12%.

The 1990s is known in Japan as “The Lost Decade” but the country struggled with bouts of deflation and disinflation well into the 2010s. It took the supply chain disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic for businesses to start raising prices and profit margins, without alienating consumers. This has translated to renewed optimism in the Nikkei 225, but the index remains 20% below its 1989 high.

China and Japan: Not quite the same

People are quick to compare China to Japan because of the latter’s decades of experience with deflation. Aside from being geographical neighbors, both countries were the manufacturing hubs of their time and attracted significant amounts of foreign investment.

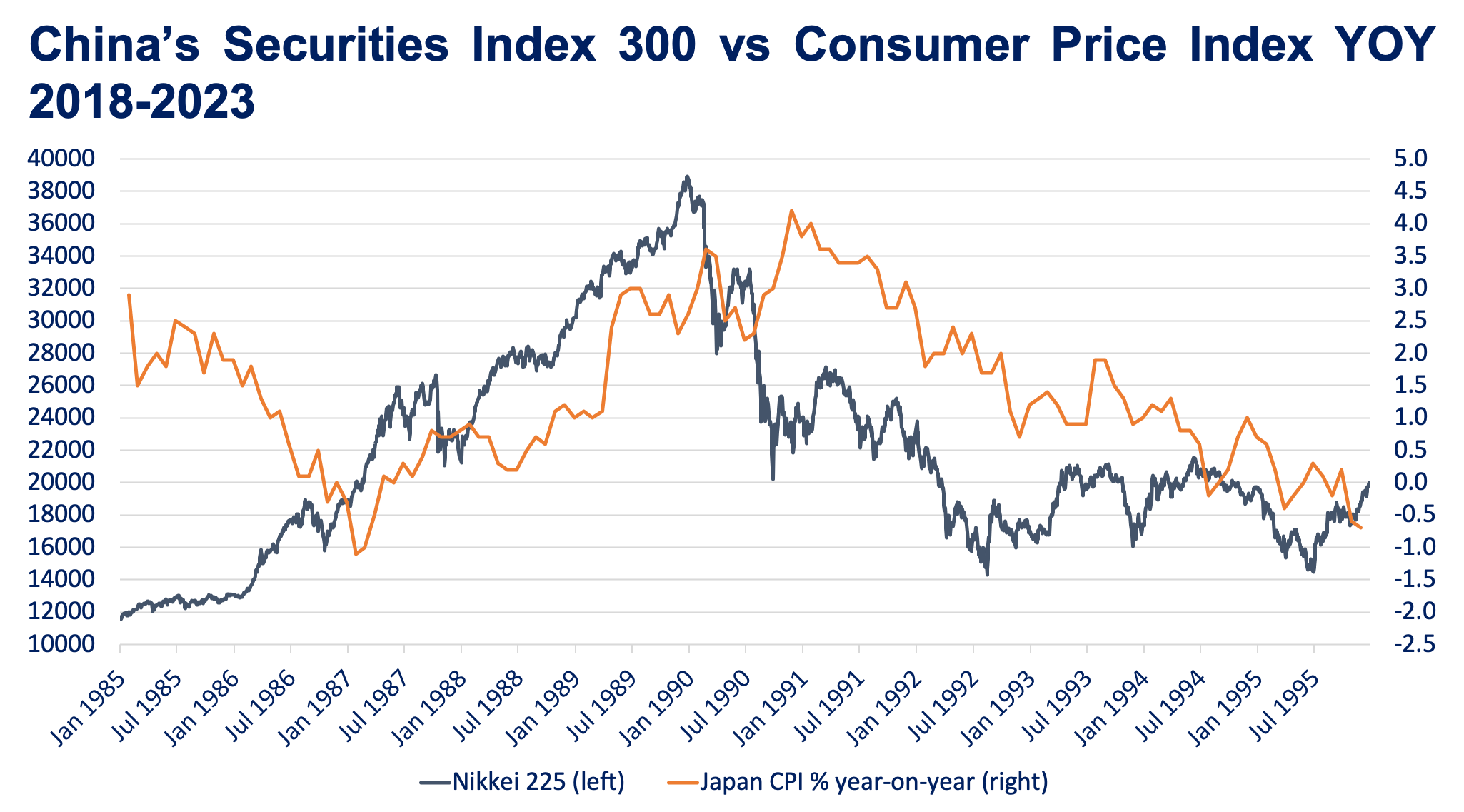

They both went on building sprees and severely overestimated the demand for real estate. Like the Nikkei 225, the China Securities Index (CSI) 300 was also on the rise and even managed to peak in February 2021 amid the pandemic but has since sold off due to loss of investor confidence, especially in the country’s inflated property sector and contentious technology sector.

But that is where the similarities seem to end.

Chart 2. China Securities Index (CSI) 300 vs. China Consumer Price Index (CPI) year-on-year 2018-2023

China’s problems today were not the result of loose monetary policy like what happened to Japan. Its economy did not overheat but rather, the country’s restrictive lockdown engineered a self-induced slowdown. To stimulate the economy, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has already cut its 1-year medium term lending facility rate from 2.75% to 2.50%. Chinese officials have recently announced plans for further monetary easing and fiscal support, which are the most appropriate actions they can take to avoid a recession. More government support was also promised for the struggling property sector to prevent more defaults.

Only time will tell if the Chinese government’s policies would help the world’s second largest economy truly recover from its post-pandemic woes. Compared to other nation’s governments, the CCP has been known for taking immediate and decisive actions with little internal resistance.

Once one of the fastest growing economies in the 21st Century, China will have to learn the hard way how to get out of a slowdown so that it does not get compared to its neighbor. As long as the country can reclaim once more its competitive advantage as the world’s top manufacturing hub and pull its property sector together, it should be able to conquer the threat of deflation.

EARL ANDREW “EA” AGUIRRE is a Market Strategist at Metrobank’s Financial Markets Sector and has 10 years of experience in foreign exchange, fixed income securities, and derivatives sales. He has a master’s in business administration from the Ateneo Graduate School of Business. His interests include regularly traveling to Japan and learning its language and culture.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By EA Aguirre

By EA Aguirre