The world is watching China’s pivot from zero-COVID

Some may rejoice over China’s decision to abandon its zero-COVID policy. However, the impact on global economies will depend on how well China manages the said pivot.

China has had one of the most stringent COVID-19 measures in the world for nearly three years, aptly called the “zero-COVID” policy.

This policy is characterized by regular polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, which are usually required before entering a facility; isolation at a government quarantine facility for potential or suspected cases; immediate lockdowns of buildings, communities, or even entire cities; and the closing of borders to most international visitors, among others.

This zero-COVID strategy has severely affected not only China but also the rest of the world. As a major trading partner of global economies as evidenced by its “Made in China” trademark, its lockdowns have affected factory activities and operations in key ports, causing its exports to slump. Imports have also fallen because of low consumption demand amid COVID-19 curbs and lockdowns.

Moreover, it was pointed out that when China contracts by 1%, the global economy shrinks by half a percentage point; that’s how big China’s influence is on the global economy. Because of this important role, China’s situation also affects the global prices of key commodities such as oil.

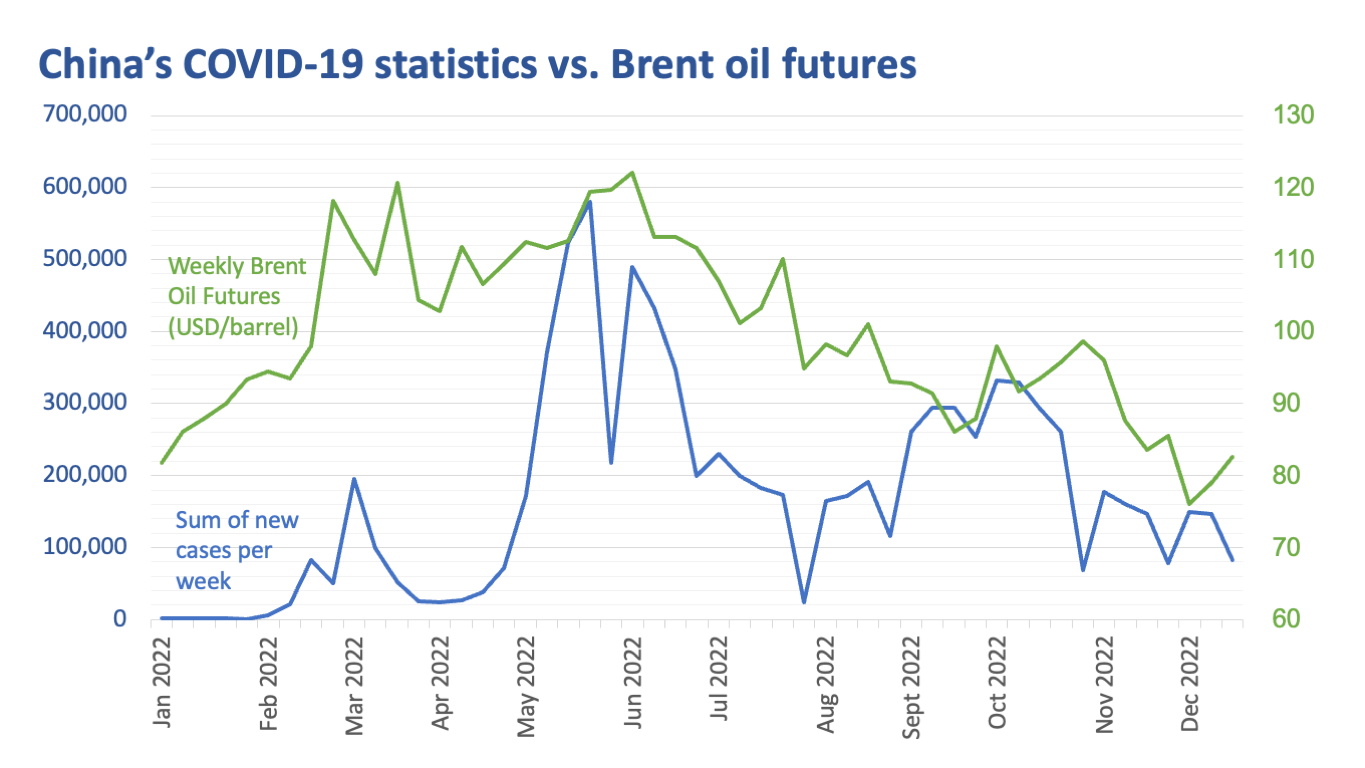

When China relaxes COVID-19 curbs, oil prices rise as markets become optimistic about the country’s reopening. However, because of low vaccination rates, cases also spike. Because of this, strict lockdowns are reinstated, and what usually follows is a fall in energy prices due to recession worries. (Data from the World Health Organization as of December 22, 2022)

Is China prepared for a drastic pivot?

On December 7, China announced some substantial and drastic changes to its COVID-19 policy. Infected people are now allowed to stay at home (not in a government facility). Testing and mandatory quarantine for cross-regional travel are no longer required, as are negative test results or health code scans for entering most public places. Lockdowns are only enforced in high-risk areas and imposed in smaller scopes (e.g., lockdown of a single building or floor instead of the whole residential complex).

However, because the zero-COVID policy has been in force for so long, China lacks herd immunity, with infection rates only at around 0.13%. Moreover, China has low vaccination rates among the elderly and vulnerable (only 40% of those aged 80 and above had received a booster by late November).

Since the policy shift, there have been only a few officially reported deaths, but many are doubting this figure. China’s official cumulative death toll since the outbreak of COVID-19 is just over 5,000 deaths, but the WHO reports that there have been 31,341 deaths already since January 3, 2020.

Outlook

COVID-19 cases as well as deaths are seen to spike after this policy shift. As much as 60% of the population could be infected before stabilizing, and the cumulative death toll is seen to reach about a million by next year, according to various research studies. If this happens, this could delay or limit the benefits of reopening, and consumption may remain low.

Energy prices initially rose due to optimism about the country’s easing of COVID-19 curbs, but lackluster demand and depressed growth due to the high number of cases and deaths may leave oil prices minimally changed in the coming months.

We are already seeing this, where news of a spike in COVID-19 cases, crowded crematoriums and funeral homes, long lines at the hospital, and dwindling medicine supplies in China have kept oil prices from rebounding substantially. This might translate to lower inflation in the Philippines in the near term because of depressed energy prices.

However, if COVID-19 cases and deaths become relatively stable soon, energy prices may rebound and recover due to higher demand. This may lead to an inflation surge due to the acceleration in consumption. Central banks around the world, including the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), may then need to continue hiking policy rates for a much longer time to rein in consumption and arrest rising prices.

And with China being the world’s biggest importer of natural gas, the global energy crunch may worsen, as China imports more and reduces supply away from Europe and other Asian nations, including the Philippines.

Whatever effect the policy pivot has on the world, a lot will depend on how well China manages and handles the transition to its reopening.

ANNA ISABELLE “BEA” LEJANO is a Research & Business Analytics Officer at Metrobank, in charge of the bank’s research on the macroeconomy and the banking industry. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Business Economics from the University of the Philippines School of Economics and is currently taking up her Master’s in Economics degree at the Ateneo de Manila University. She cannot function without coffee.

DOWNLOAD

DOWNLOAD

By Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano

By Anna Isabelle “Bea” Lejano